Just when you think you’ve got a grasp on US copyrights, and have checked through all the records for the author or their estate filing renewals, another quirk raises its head. The author is not always the only one with the power to renew and that renewal doesn’t even have to be direct. If the work was published in a periodical or other collective work, frequently a pulp magazine in my case (although this applies to newspapers, anthologies, encyclopedias, and many other types of publication), then the publisher might have the authority to renew the copyright as well.

This has actually been brought up here before in my post about Philip K. Dick’s Time Pawn being deleted.

As far as I can tell, prior to 1978, the publisher of a periodical was presumed to acquire all rights from the author when they purchased a work for publication, unless a contract between them explicitly stated otherwise. There appears to be an associated situation where a periodical publishing a licensed work without the author’s copyright notice would put that work into the public domain (if it was the first publication of that work; first publication is the important one legally, the point at which it is fixed in tangible form).

One key piece of case history seems to be Goodis v. United Artists Television, Inc. (a 1969-70 case), which includes the finding “where a magazine has purchased the right of first publication […] copyright notice in the magazine’s name is sufficient to obtain a valid copyright on behalf of the beneficial owner, the author or proprietor.”

Without knowledge of the precise details of any contract, many works can theoretically be under two separate copyrights at the same time: author and publisher. If the author allowed the copyright to lapse, but the issue of the magazine had its copyright renewed, then the work is still copyrighted. If the publisher allowed the copyright on the issue to lapse, but the author renewed the copyright, then the work is still copyrighted. If both renewed, the two parties probably need to retain lawyers to work things out between themselves but Wikisource and the public domain are almost definitely out of luck; the work is still copyrighted.

As far as Wikisource is concerned, without evidence to the contrary, the project must assume the worst case (from the project’s point of view), that either or both copyrights are valid.

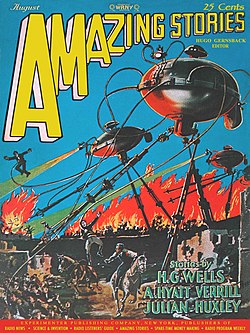

Cases where the periodical’s copyright have lapsed but individual works have not are some of the most awkward for me. The owners of Weird Tales and Amazing Stories almost never renewed their own copyrights (probably because both changed hands a few times over the years), so most of the individual issues are broadly in the public domain. However, individual authors sometimes did renew specific works, meaning that a single short story in the magazine is under copyright while the rest is not. Rather than writing off the entire thing, I have redacted the scans, when I upload them, to omit the copyrighted parts. This is even more awkward when the copyrighted work shares a page with a public domain piece.

Sometimes the opposite is true. The author hasn’t bothered to renew for whatever reason but the magazine has. In particular, I know this applies to a few of the works of Howard and Lovecraft. In the same way, a lot of Golden Age science fiction is off-limits because the other two of the Big Four SF magazines, Astounding Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories (along with the rest of the Thrilling range), did renew their copyrights at the magazine level.

With periodicals, both have to be checked before they can be transcribed to Wikisource and released into the wild.